|

|

The tranquility of the Arawaks would not last for long. They were followed by another Amazonian group, the Caribs. A warrior people, the Caribs steadily pushed the Arawaks off St. Maarten and took the island for themselves--only to lose it in turn to the Europeans. Christopher Columbus sighted the island on November 11, 1493, the holy day of St. Martin of Tours. He claimed it for Spain the same day, and it is from this day that the island bears its name.

Events in Europe soon affected the island's destiny. With the end of the Eighty Years' War between Spain and the Netherlands, the Spanish no longer needed a base in the Caribbean. They left St. Maarten, and the island was soon claimed by both the French (who sailed over from St. Kitts) and the Dutch (from St. Eustatius). After some skirmishes, the two powers signed a treaty in 1648 which divided the island between them. Although its historical truth is somewhat less than ironclad, local legend claims that a Dutchman and Frenchman stood back to back and walked in opposite directions around the shoreline, drawing the boundary from the spot where they met. As for why the French ended up with more land, the story notes the Dutchman's progress was slowed by the large quantity of Geneve that he required for the walk. The neighbours did not coexist peacefully at first, and the territory changed hands sixteen times between 1648 and 1816. Nonetheless, the Dutch side of the island soon became an important trading center for salt, cotton, and tobacco. Wealth also arrived with the establishment of sugar plantations, worked by slave labor. When slavery was abolished in the mid-19th century, the plantations closed down and St. Maarten's prosperity ended. For the next one hundred years, the island sank into an economic depression.

|

. |

|

This page, and all contents

of this Web site are Copyright (c) 1996-2010 by interKnowledge

Corp. All rights reserved. |

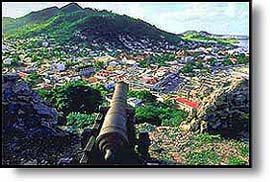

Obsessed

with the greater conquests of Mexico and South America, the Spanish

ignored St. Maarten. It was virtually forgotten by Europeans until

the 1620s, when Dutch settlers began extracting salt from St. Maarten's

ponds and exporting it back to the Netherlands. The island's commercial

possibilities soon caught the attention of the Spanish, who drove

off the Dutch in 1633 and erected a fort to assert their authority.

Known as the Old Spanish Fort, this bastion still stands at Point

Blanche. In 1644, a Dutch fleet under the command of Peter Stuyvesant

attempted unsuccessfully to retake the island. Stuyvesant, who

later became governor of New Amsterdam (present-day New York),

lost a leg to a Spanish cannonball during the fighting. Although

Stuyvesant was buried in New York, his leg rests in a cemetery

in Curaçao.

Obsessed

with the greater conquests of Mexico and South America, the Spanish

ignored St. Maarten. It was virtually forgotten by Europeans until

the 1620s, when Dutch settlers began extracting salt from St. Maarten's

ponds and exporting it back to the Netherlands. The island's commercial

possibilities soon caught the attention of the Spanish, who drove

off the Dutch in 1633 and erected a fort to assert their authority.

Known as the Old Spanish Fort, this bastion still stands at Point

Blanche. In 1644, a Dutch fleet under the command of Peter Stuyvesant

attempted unsuccessfully to retake the island. Stuyvesant, who

later became governor of New Amsterdam (present-day New York),

lost a leg to a Spanish cannonball during the fighting. Although

Stuyvesant was buried in New York, his leg rests in a cemetery

in Curaçao. The

situation began to change in 1939, when all import and export

taxes were rescinded and the island became a free port. Princess

Juliana International Airport opened in 1943, and four years

later the island's first hotel, the Sea View, welcomed its first

guests. In the next few decades, St. Maarten boomed as an international

trading and tourism center. Today, Dutch St. Maarten has nearly

3,000 hotel rooms and is visited by hundreds of thousands of

people each year.

The

situation began to change in 1939, when all import and export

taxes were rescinded and the island became a free port. Princess

Juliana International Airport opened in 1943, and four years

later the island's first hotel, the Sea View, welcomed its first

guests. In the next few decades, St. Maarten boomed as an international

trading and tourism center. Today, Dutch St. Maarten has nearly

3,000 hotel rooms and is visited by hundreds of thousands of

people each year.